ESG bonds: differences, current market situation, and challenges facing investors

By Jonathan Capelo

When we talk about ESG fixed income, the first thing that usually comes to mind is environmental bonds, also known as green bonds. However, there are other categories within the ESG universe that pursue other sustainable objectives. According to the classification of the International Capital Market Association (ICMA), the entity that establishes the guiding principles for this type of vehicle, ESG bonds are divided into four main groups: green bonds, social bonds, sustainable bonds, and sustainability-linked bonds, depending on the purpose that the issuing company seeks to finance. For example, green bonds finance projects related to energy efficiency, renewable energy, or waste management. Social bonds are used for initiatives such as education, financial inclusion, or affordable housing. Sustainable bonds combine both, while sustainability-linked bonds do not finance a specific project, but link the final interest rate to objectives previously defined by the issuing company, such as reducing CO₂ emissions, creating jobs, or achieving gender parity in management positions. In other words, if these targets are not met, the issuer must pay a higher interest rate. New forms of sustainable financing have recently emerged, such as transition bonds, issued mainly by companies in carbon-intensive sectors seeking financing by committing to reduce their emissions.

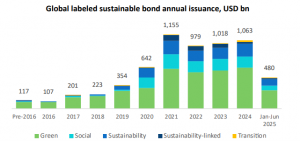

According to the latest World Bank report on sustainable bonds, in the second quarter of 2025, the total volume of ESG bonds (including green, social, sustainable, and sustainability-linked bonds) reached US$6.3 trillion. Although green bonds continue to account for the majority of issuances, it is essential for investors to be aware of the available alternatives and the key differences between them.

Source: World Bank. Labeled Bond Quarterly Newsletter Issue No 12

Several relevant conclusions can be drawn from the latest World Bank study for the second quarter of 2025. In general, the ESG bond market is showing signs of stabilization. Although green bonds continue to lead this market, issuances in other categories have grown significantly, especially since 2020, driven by COVID-19 and the need to finance social projects by national and supranational governments and corporations. While growth in developed markets was remarkable and has now stalled, ESG bonds are consolidating their position as a key financing channel in emerging markets, with non-green bonds playing a particularly prominent role. Finally, sustainability-linked bonds have declined in popularity, partly due to regulatory changes that require greater transparency and rigor.

As with any investment opportunity, these types of instruments carry certain risks that must be carefully evaluated. One of the main challenges is the aforementioned regulation and lack of uniformity, as it is still under development and subject to frequent changes, especially with regard to ESG criteria. Something similar happened with the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) for funds and ETFs, which has generated controversy due to greenwashing practices, appearing to be sustainable without actually complying with the required standards.

How can investors tackle these new challenges? Having an independent advisor specializing in sustainability is key to guiding clients in investing in these bonds. Conducting a more in-depth analysis and not just focusing on the green or social label. For institutional and private clients with ESG preferences, these bonds represent an essential investment that complements the rest of the traditional assets in their portfolio. It is therefore essential to link the investment to key concepts such as intentionality, additionality, and materiality, thus ensuring that the client is genuinely aligned with their mission, vision, and values. An illustrative example can be found in religious entities, which repeatedly ask us for a detailed analysis of their investment portfolios. We observe that in most cases their investments do not match their objectives and beliefs because, despite applying exclusion or ESG criteria, they are not aligned with the Social Doctrine of the Church.

Some best practices include evaluating the destination of funds, the credibility of the issuer, and the alignment of the issuance with recognized standards, conducting the study not only before purchase but periodically, verifying that impact metrics are met and are quantifiable, comparable, and transparent. In addition, prioritize issuances that have external audits and adhere to frameworks such as the ICMA principles or the Climate Bonds Initiative standards. Finally, consider that more recent issuances are often subject to stricter criteria, which may offer greater regulatory certainty.